Rae Lyn Conrad Burke (1966, NV): A Life of Inquiry and Adventure...But No Fairy Tale Ending

by Dr. Regis Kelly*

On first meeting with Rae Lyn Burke you might be impressed by her small stature, graciousness, and modest demeanor. She might strike you as a surprising choice for a U.S. Presidential Scholar. That perception vanishes once you know her well, explore her colorful history, learn of her contributions to biotechnology, and appreciate the changes she has helped promulgate in attitudes toward women scientists and brain disease.

Rae Lyn Conrad (now Burke, 1966, NV) grew up largely in Reno, the first child of two modest school teachers. Her teacher parents probably explain Rae Lyn’s grammatical precision and articulate speech. Marian, her mother, was a major political figure, rising to be the head of a national retired teachers association and, in that role, interacting in person with President Bill Clinton. Since Marion was raised a Mormon, Rae Lyn too was an enthusiastic Mormon in her early years. Although respectful of the Mormon commitment to charity, hard work, and family, the free-spirited Rae Lyn quickly ran afoul of its moral strictures. Ever the rebel, she would escape from her basement bedroom window for romantic assignations, perhaps without her parents knowing even years later.

Growing up in Reno allowed Rae Lyn to develop skills in horsemanship. One of her horse riding jobs in high school was to corral bulls and collect their semen. Living near Mount Rose, she also became a superb skier and a ski instructor. In those days, women skiers were assigned to teach the five-year olds. Rae Lyn had other ideas, including attracting the attentions of good men skiers. Once Rae Lyn attempted to parade her talents for a particularly appealing young man, only to end up in an accident resulting in two broken bones in her lower leg and six months in the hospital—where that attractive young man did indeed visit her.

Rae Lyn Conrad, high school graduation

While living a free-spirited life, Rae Lyn quietly applied her impressive brain power and meticulous organizing skills to her studies, resulting in her selection as one of the two Presidential Scholars from Nevada in 1966 and her thrilling meeting with President Lyndon Johnson. Her academic skills also led to her acceptance at Berkeley as an undergraduate. However, family pressure, particularly a concern about Berkeley’s reputation for radical activities, pushed her instead toward the University of Nevada in her hometown of Reno, where she studied chemistry. At the university she became a member of the gymnastics team, specializing in parallel bar routines. Few people achieve such a combination of athletic and academic excellence. To compensate for having to live at home as an undergraduate, Rae Lyn spent her summers far from home, working at Oak Ridge National Laboratory one summer and in a morgue another. Ever willing to take risks, she traveled around by hitchhiking. Her enthusiasm for hitchhiking diminished, however, after she had to jump from a moving truck to avoid an overly amorous truck driver.

Rae Lyn began her PhD in chemistry in an excellent department in Boulder, Colorado. Her interests began to move from strict chemistry to the increasingly exciting field of DNA. Away at last from her home, she developed an intense social life with fellow outdoors enthusiasts and party-loving fellow students. Parties were wild but not always fun. One evening her male friends noticed the fine collection of fish in her aquaria and made a game of swallowing them live. Sheepishly they returned the next day with fish in plastic bags to help restore her collection.

Rae Lyn got a greater appreciation for life on the East Coast when her advisor moved his lab to Stony Brook, on Long Island. She liked it so much there that she applied to continue her DNA studies as a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton in the lab of an up-and-coming young molecular biologist, Bruce Alberts. Rae Lyn’s choice of a mentor was superb. Bruce eventually became president of the National Academy of Sciences, editor of Science magazine, and a Lasker awardee. But her goal of staying on the East Coast was thwarted. Bruce accepted a position in the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), and Rae Lyn found herself on the West Coast. Her husband at the time, fellow scientist David Burke, moved with her.

Rae Lyn arrived at UCSF at a particularly exciting time. Bruce Albert’s mastery of the enzymology of DNA synthesis was complemented by Herb Boyer’s skill in cloning DNA, Howard Goodman’s expertise in nucleic acid sequencing, and Bill Rutter’s appreciation of the value of cloning the genes of hormones such as insulin. Rae Lyn fitted in immediately, spending long hours in the cold room achieving remarkable success in purifying important proteins and recording it all with a meticulous precision that made her notebooks prime exhibits in future patent fights. Her future after UCSF was not so clear, however. Most science faculties had few to no women. Indeed UCSF at the time was—reluctantly—hiring its first female faculty member in the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics. There was another option, however, that seemed even riskier for a woman than seeking a faculty position. Some faculty members were taking their first tentative steps toward creating a biotechnology start-up. At that time, the future of biotechnology seemed as dubious as putting a human on Mars. Showing again her quiet fearlessness and penchant for risk-taking, Rae Lyn left UCSF to be employee number six at Bill Rutter’s new startup, Chiron.

Chiron eventually grew to thousands of employees and was acquired by Novartis for billions of dollars. The early days were, however, rocky and uncertain. With her work habits, Rae Lyn was an essential part of the early small team. When, therefore, she announced that she was pregnant, her bosses were critical of her decision, telling her that her career was essentially over. But times had changed, at least a little. Rae Lyn responded by doubling her efforts and working hard to the very end of her pregnancy. After giving birth to her daughter, Dylan, Rae Lyn took only two weeks off from work before returning to her bench at Chiron. Rae Lyn consistently regretted her decision to short-change the experience of motherhood for her job, but to many of her women scientist colleagues fighting for recognition in a world overwhelmingly dominated by men, Rae Lyn was a hero.

Rae Lyn grew to a position of increasing respect during the fifteen years she spent at Chiron. The program she headed, creating a vaccine against the herpes virus, was the first Chiron project to progress to Phase III clinical trials in humans. With bated breath, Chiron awaited the results of its decade-long program and $120 million investment. The trial failed to meet its benchmarks. Consternation was everywhere and a scapegoat was needed. Despite her deep commitment to Chiron and her project, Rae Lyn was fired.

Rae Lyn was distraught that Chiron had rejected her after so much loyalty, but she is tough. Given her deep practical knowledge of vaccine development, she was able to put together a consultancy group that was soon generating as much income as Chiron had been giving her. Ironically, as we shall see later, she was the vaccine consultant to the firm Elan, which was developing a vaccine that they hoped would reduce amyloid plaque in patients' brains and thus cure Alzheimer’s.

One of the groups she consulted with was SRI, originally the Stanford Research Institute. Recognizing her talents, SRI recruited Rae Lyn as director of their Infectious Diseases Division, which she built into one of the best-funded research groups at SRI. As at Chiron, she was loved and respected as a boss by her staff, who have remained remarkably loyal to her over the years.

Although a scientific success during these years, Rae Lyn was not a scientific nerd. In addition to being an ardent opera fan for thirty years, she bought and equipped two sailboats and learned to be an ocean sailor. With her family, she scuba dived in Sulawesi, trekked through remote villages in Laos, climbed to Buddhist shrines at the mountainous Sikkim-China border, and visited, with an armed guard, remote, mine-protected archeological sites in Cambodia, before the guerrilla war there had ended.

As her daughter, Dylan, and stepson, Colin, were growing up, Rae Lyn was the endlessly fun-loving mother who encouraged creative games and exciting adventures. At the same time she concealed her reluctance to be seen as a "mere wife" in order to be a gracious host when her husband, Regis Kelly, had to entertain as a departmental chairman and executive vice chancellor.

This may sound like a fairy tale life but the ending is not out of Disney.

Almost ten years ago, while Rae Lyn’s career at SRI was growing by leaps and bounds, she was diagnosed at age 58 with early onset Alzheimer’s. Gone were her driver’s license, her job, and the privilege of feeling useful to society.

Her contacts in the medical world persuaded her to sign up for what looked like a very promising clinical trial. Here she found herself being injected with a successor to the vaccine she had helped develop at Elan. The trial failed to have efficacy.

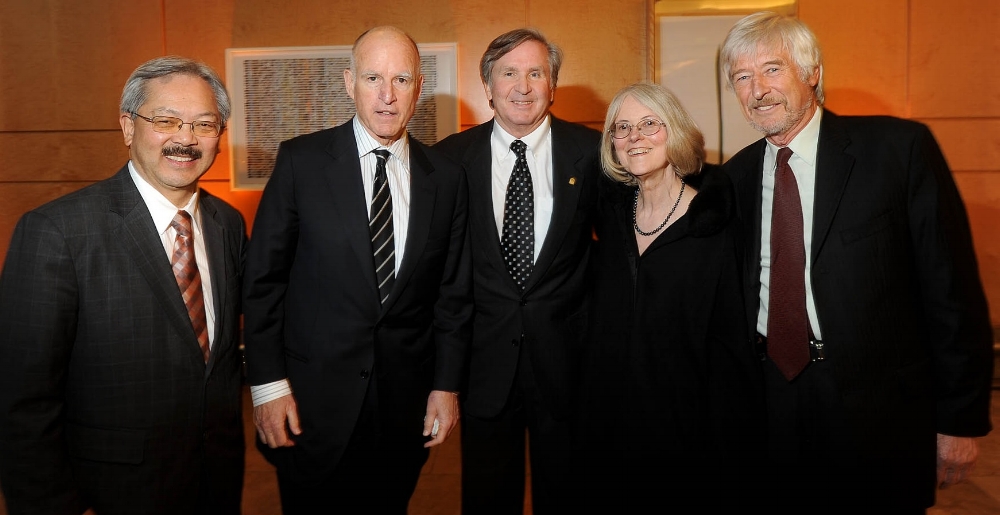

Rae Lyn was an honored guest at the opening of a new hospital at Mission Bay, San Francisco, in 2014. (left to right): Ed Lee, mayor of San Francisco; Jerry Brown, governor of California; Brook Byers, renowned venture capitalist; Rae Lyn; Dr. Regis Kelly.

For a time, while her public speaking skills were still sufficient, she became a popular and effective advocate for Alzheimer’s research. She still looked vibrant and her story was a poignant one. It is hard to imagine how greatly she struggled to stand behind the podium and address an audience, not as a successful scientist, but as someone whose verbal and intellectual skills were obviously deteriorating. But she hoped to emulate the courage of early AIDS patients who similarly were open about their disease and gave up their privacy to attract attention to their affliction. For some years Rae Lyn was the topic of touching articles which alerted the public to a destructive future that faced so many of them, as long as no cure was available. Her daughter, Dylan, was even recruited as an advisor to the 2014 feature film on Alzheimer’s disease Still Alice.

Nowadays, although Rae Lyn retains an appearance of health, her days at home are quiet, enlivened by a resourceful caregiver and occasional visits from family and old friends from work. She is no longer the brilliant, meticulous planner she once was, but all who meet her remark on her graciousness, her modesty, her smile, and her earthy sense of humor.

________

*Dr. Regis Kelly is the director of one of four California Institutes for Science and Innovation, created by the California legislature to strengthen the academic foundation of its technology-based industries. From 2000 to 2004, Dr. Kelly served as Executive Vice Chancellor at the University of California in San Francisco, where his major responsibility was the new Mission Bay campus. His academic research was in the field of molecular and cellular neurobiology. In 2014 he was appointed an officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for services to science, innovation, and global health. He is Rae Lyn's husband.